Reading Sekula over spring break was a really interesting experience because it made my try to consider everything as an archive, or at least try to. Some things were easy menus, newspapers, the internet and the like all presented pretty straightforward cases for being archives. Then I started thinking that almost anything can be an archive depending on how one thinks of the criteria or defines the parameters of an archive. I was thinking of a folder I’ve kept on my computer called “pics” that I’ve had pretty much since the I first got the internet in 5th grade. In it I’ve kept almost every snapshot, news photo, celebrity photo, or any image that I’ve ever thought I might want to look at again. Its sort of funny because I pretty much never look through these pictures and I suppose the parameters of this archive would be anything I saw online that I thought for a second I might want to one day look at again. It is organized chronologically because that’s the way I set up the folder but it works in almost exactly the way Sekula describes as far as abstracting context, changing meaning and re-making the meaning of everything to be somewhat antagonistic to whatever its next to. I also think of it as something of a bizarre self portrait because the images do very literally reflect my visual interests. There is lots of friends, lots of family, lots of pictures of my beloved Steelers, and more than a few images of pretty girls who I have no idea who they are.

As far as archives in art I kept thinking about Christian Boltanski and the archives he manipulated and made. I think the most interesting and haunting to me is Sans Souci, a book of images he made from photographs of young Nazis on vacation and relaxing and smiling. The idea that something evil is absolutely haunting and I have to say after having seen it I can’t really look at any family album the same way again. You sort of always know when you look at a photo that you really cant tell anything about the person from it but that a normal looking person could be so menacing is rather terrifying

Tuesday, March 30, 2010

Tuesday, March 16, 2010

One quote from this weeks readings stood out to me as kind of summarizing all my feelings about everything we have encountered in this class, and perhaps just everything ever. It was from Jameson’s Postmodernism or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. It comes during a section where he is urging us not moralize the postmodern condition, which he points out is very difficult, nearly impossible. “We are somehow to lift out minds to a point at which it is possible to understand that capitalism is at one and the same time the best thing that has ever happened to the human race, and the worst.” I suppose for me this sentence, and the non-judgmental stance of the section of the essay, was at odds with my conceptions of critical theory of postmodernism. By this I mean that every invocation within art-discourse experience about postmodernism is chalk full of moral judgment, usually someone either for or against likening postmodernism or its destruction to a moral imperative. I found Jameson’s words acutely summed up my own feelings towards capitalism quite powerfully. I reap the benefits and suffer the indignities of late capitalism equally on a personal level and on a global level I can understand its glories and evils in nearly equal measure. That said I will be needing to read his section on mapping again before class, I got bogged down pretty badly there.

On Douglas Crimp’s Appropriating Appropriation I had some sympathy towards his argument but he also did something I find really frustrating among art historians which is making a case that is weak and then cherry picking examples as marshaled evidence for his thesis. For example in his polemic on Ghery and Graves his argument that Ghery’s appropriations were lateral and therefore good and Graves were historical and therefore bad seemed to oversimplify some aspects of creation to. I’m not sure how to articulate this clearly but I’m not sure that historical appropriation is the only thing, or has anything to do with why I don’t Like Graves’ buildings. On the flip side I don’t like any of Ghery’s buildings either and if I did I doubt its because I suddenly saw the intellectual beauty of corrugated steel as loopy siding. This is always where postmodernism arguments lose me (well not only here) that they always seem to hinge on architecture as the best or first or quintessential case study for proving some paramount fact. I suppose I don’t understand architecture very well (my fondness for the Harold Washington Library should be proof enough of that.) When I look at Grave’s Art Center in Minneapolis I am disinterested in what looks to me like too much a tamed Ellsworth Kelly or Joseph Albers painting. I don’t mind the historical appropriation, I just don’t like the way it was done.

On Douglas Crimp’s Appropriating Appropriation I had some sympathy towards his argument but he also did something I find really frustrating among art historians which is making a case that is weak and then cherry picking examples as marshaled evidence for his thesis. For example in his polemic on Ghery and Graves his argument that Ghery’s appropriations were lateral and therefore good and Graves were historical and therefore bad seemed to oversimplify some aspects of creation to. I’m not sure how to articulate this clearly but I’m not sure that historical appropriation is the only thing, or has anything to do with why I don’t Like Graves’ buildings. On the flip side I don’t like any of Ghery’s buildings either and if I did I doubt its because I suddenly saw the intellectual beauty of corrugated steel as loopy siding. This is always where postmodernism arguments lose me (well not only here) that they always seem to hinge on architecture as the best or first or quintessential case study for proving some paramount fact. I suppose I don’t understand architecture very well (my fondness for the Harold Washington Library should be proof enough of that.) When I look at Grave’s Art Center in Minneapolis I am disinterested in what looks to me like too much a tamed Ellsworth Kelly or Joseph Albers painting. I don’t mind the historical appropriation, I just don’t like the way it was done.

Likewise with Ghery its not that I have strong feelings for lateral appropriation one way or the other it just seems like using everyday construction materials to make self consciously beautiful forms for super high minded structures gives me a difficult to articulate feeling of trying too hard.

So when he talks about Robert Mapplethorp’s historical appropriation as being somehow lesser than Sherrie Levine’s wholesale and lateral appropriation my reaction was something like, but who cares? Mapplethorp’s images are rich to me for their reaching back into the past for visual style and the elegance and beauty he executes his images with further add to this. Also I really like Sherrie Levine but I suppose I don’t see the practices as being as opposed to each other as some. This Mapplethorp reference to this Munch print is my favorite.

So when he talks about Robert Mapplethorp’s historical appropriation as being somehow lesser than Sherrie Levine’s wholesale and lateral appropriation my reaction was something like, but who cares? Mapplethorp’s images are rich to me for their reaching back into the past for visual style and the elegance and beauty he executes his images with further add to this. Also I really like Sherrie Levine but I suppose I don’t see the practices as being as opposed to each other as some. This Mapplethorp reference to this Munch print is my favorite.

I also liked the Art Since 1900 chapter on the legacies of photo conceptualism. I had never really though of people like Rosler and Sekula as being politicized versions of Ruscha and Baldassari but that argument makes a lot of sense. I do sort of artists in those terms a lot though, like Gonzalez Torres as a more soulful and political version of Minimalism or Jenny Holzer as a more poetic or energized version of Mel Bochner. Well that’s not fair, I love Mel Bochner, but you know what I mean.

Ok so now on to the image as text, I would like to try to analyze something a little on the tricky side but it is something I have been thinking about pretty much constantly since I first saw it a few weeks ago at the Whitney. The Piece is called “We Like America and America Likes Us” by an anymous artist collective called the Bruce High Quality Foundation. Already we have two references at least, the title of the piece a reference to Joseph Beuys’ performance from 1974 called “I Like America and America Likes Me” where he traveled from the airport by ambulance to an art gallery that he shared with a coyote for three days, befriends the animal, performs some rituals, and then travels back to Germany, getting to the airport again, in an ambulance. The Bruce, in BHQF is reportedly a reference to Bruce Nauman, but I’m not sure of that. So the piece is a sculpture a found object that is a part ambulance part hearse. It is all white, its healights are on and on its windshield is a video projection.

The projection is a mixed bag of American movies, television, youtube clips, and news footage from the past 25 or so years, These references are chaotic and fast paced and beyond that is a female voice over that reads a long kind of Whitmanesque letter to America. The letter addresses America as a partner in every kind of relationship, from loving, to abusive, from lover, to parent and child etc. The language slips in and out of genders and goes for over half an hour. Here are some parts I found transcribed.

We like America. And America likes us. But somehow, something keeps us from getting it together. We come to America. We leave America. We sing songs and celebrate the happenstance of our first meeting – a memory reprised often enough that now we celebrate the occasions of our remembrance more often than their first cause.

We wished we could have fallen in love with America. She was beautiful, angelic even, but it never made sense. Even rolling around on the wall-to-wall of her parents’ living room with her hair in our teeth, even when our nails trenched the sweat down his back, and meeting his parents, America stayed simple somehow. He stayed an acquaintance, despite everything we shared. Just a friend. We could share anything and it would never go further than that.

No one really knows how love begins. A look on his face one time after we’d made love – a text message too soon after the last one. When did we become a thing to hold on to rather than just something to hold? We didn’t know America was in love with us until it was too late. Maybe we couldn’t have done anything about it anyway. America fell in love with the idea of us, with some fantasy of us, some fantasy of what America and us together would be, before we had a chance to tell him it could never work, we weren’t ready for a relationship, we weren’t comfortable being needed, we didn’t have the resources to be America’s dream.

It wasn’t easy letting America down. As we stuttered through our rehearsed speech we watched the change on her face. We could see the zoom lens of her attention clock away. We could feel ourselves receding back into the blur of the general population.

There was a time we thought we were nothing without America. When she left, we realized all the excuses we’d been making. All the problems we’d been trying not to address. We drunk dialed our memory of America just to hear what we were thinking. We worked late and we told ourselves we had to, that the work came first, that this was an important time in our lives and that love could wait. Just wait a little longer and we’d fix everything, we’d say. Solving the America problem, our lack of attention, our disinterest in sex, our never being home, our thinking of her as a problem – it would have to wait.

So why I’m having such a tricky time reading this piece as text is one, there is literally a text in it, which may break the rules a bit for this assignment but the text is at once very poetic and beautiful and also very generic. For example I am able to understand the different passages because I know them, or I understand the situations they evoke from my lived experience (“No one really knows how love begins, a text message too soon after the last one.”) but mostly I know these sentiments through American popular culture. The workaholic, and the abusive parent or disinterested lover are things I know from texts like television and movies which are the things that are playing on the windshield. It made me question how I know about love and if American popular culture isn’t completely responsible for every part of it. And is it a hearse there till kill the culture or an ambulance there to save it? Which should it be?

We like America. And America likes us. But somehow, something keeps us from getting it together. We come to America. We leave America. We sing songs and celebrate the happenstance of our first meeting – a memory reprised often enough that now we celebrate the occasions of our remembrance more often than their first cause.

We wished we could have fallen in love with America. She was beautiful, angelic even, but it never made sense. Even rolling around on the wall-to-wall of her parents’ living room with her hair in our teeth, even when our nails trenched the sweat down his back, and meeting his parents, America stayed simple somehow. He stayed an acquaintance, despite everything we shared. Just a friend. We could share anything and it would never go further than that.

No one really knows how love begins. A look on his face one time after we’d made love – a text message too soon after the last one. When did we become a thing to hold on to rather than just something to hold? We didn’t know America was in love with us until it was too late. Maybe we couldn’t have done anything about it anyway. America fell in love with the idea of us, with some fantasy of us, some fantasy of what America and us together would be, before we had a chance to tell him it could never work, we weren’t ready for a relationship, we weren’t comfortable being needed, we didn’t have the resources to be America’s dream.

It wasn’t easy letting America down. As we stuttered through our rehearsed speech we watched the change on her face. We could see the zoom lens of her attention clock away. We could feel ourselves receding back into the blur of the general population.

There was a time we thought we were nothing without America. When she left, we realized all the excuses we’d been making. All the problems we’d been trying not to address. We drunk dialed our memory of America just to hear what we were thinking. We worked late and we told ourselves we had to, that the work came first, that this was an important time in our lives and that love could wait. Just wait a little longer and we’d fix everything, we’d say. Solving the America problem, our lack of attention, our disinterest in sex, our never being home, our thinking of her as a problem – it would have to wait.

So why I’m having such a tricky time reading this piece as text is one, there is literally a text in it, which may break the rules a bit for this assignment but the text is at once very poetic and beautiful and also very generic. For example I am able to understand the different passages because I know them, or I understand the situations they evoke from my lived experience (“No one really knows how love begins, a text message too soon after the last one.”) but mostly I know these sentiments through American popular culture. The workaholic, and the abusive parent or disinterested lover are things I know from texts like television and movies which are the things that are playing on the windshield. It made me question how I know about love and if American popular culture isn’t completely responsible for every part of it. And is it a hearse there till kill the culture or an ambulance there to save it? Which should it be?

Tuesday, March 9, 2010

After finishing The Originality of the Avant-Garde by Rosalind Krauss I was struck by most by how second nature all her arguments seemed to me already. Meaning, mostly well I read the article I thought to myself on any number of points she was making, of course! Of course! Take for example all the problems with authenticity and originality she finds in Rodin’s work. (Small tangent: when I first saw The Thinker in an art book as a child I recognized it because my grandmother had a pair of The Thinker shaped book ends on her shelf. Naturally I assumed she was rich.) Locating the original of a cast sculpture is maddening, like locating an original photograph. Anything that tries to claim originality or authenticity already strikes us me phony because it has to make that claim in the first place. In other words nothing that has ever struck me as really original ever had to have someone tell me it was. That claim is always tied to market value of the work. Why is a vintage Dorthea Lange worth so much more than a library of congress print? Scarcity, of course. That Krauss chose not to pursue the idea of the original and the importance of the original as being inescapably linked to the art market struck me as a little odd. Labeling something as original is an important way of increasing its desirability and thus capital. I’m sort of fond actually of how goofy the whole enterprise of editioning photographs is. I mean the idea that someone will only print seven or ten of an image as a way to increase value is so deeply antithetical to the very nature of photography that it strikes me as so nakedly capitalistic that it’s a bit funny. The value becomes so imaginary and arbitrary that you sort of want to pinch someone and say “you realize this emperor is completely naked right?” That’s the thing is that everyone does realize this too and I’m not saying it’s a bad this, its just a little silly. In a capitalist society artists must increase their capital, I mean I made a video of appropriated digital footage that exists online ad infinitum into an edition of three DVDs…

I digress. So in the article I also was really interested in the idea of the grid, or specifically how Krauss has theorized it. I never thought of it as something that resisted language but I understand why Krauss describes it that way. A grid truly can have an all-at-onceness that language cannot. When she talked about the grids silence in opposition to narrative I pictured taking every word from a novel and assembling them as a grid. A novel speaks when you read the words one at a time, but all at once the language is inaccessible. The grid does not privilege sequence and is thus silent. I was thinking here of Hanne Darboven and how her grids overwhelm one by presenting so much information is a relatively equal was as to be impenetrable to language. Here are some shots of her incredible installation at Dia Beacon.

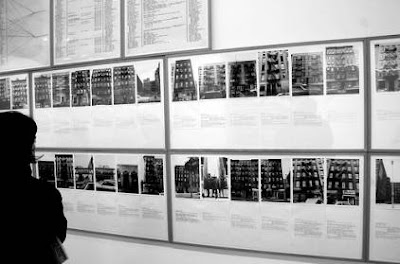

I was also thinking of Hans Haacke’s Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real Time Social System, as of May 1 1971 as a grid that tells a story, a narrative grid that would go against Krauss’ theory. After all a grid can be used to organize a narrative as well as silence one, think of course, of a comic book. Haacke’s piece is somewhat narrative but it also uses the grid to present its evidence of injustice all-at-once and give the impression that it is over whelming.

Lastly I was thinking about some of my favorite grids and copies without originals by Félix González-Torres. Especially his piles of paper that the public can take from as they like and are infinitely replenished by the museum or gallery. I wonder if they are editioned… I know his piece Perfect Lovers is editioned as three plus one artist proof but this one hanging in the office of the Renaissance Society is rumored to be an authorized exhibition copy. Also anyone with two matching clocks can have a pretty amazing forgery of this piece.

Tuesday, March 2, 2010

March 03

This week’s readings by Greenberg and Debord on kitsch and spectacle got me thinking a lot on the value of entertainment in art. In many ways I think what these articles were talking about was a certain wariness or distrust of any form of art that is too entertaining. The definition of entertaining being something along the lines of something that is easy to get absorbed in and once absorbed holds attention in such a way that is very pleasurable, causes no distress, and makes the experience of time seem to move faster. By this very definition, entertainment is very popular, if not incredibly addictive. However, according to Greenberg and Debord, this is art, or it cannot reach a very high level of art. Their definitions of art seem to demand more from a viewer than simply their attention. The avant-garde is by its nature, very challenging to its audience. It requires thought and critical interaction on some level that is less pleasurable than simply being told a really exciting story. This is also the value of the avant-garde, that it can edify you, change you in some way, where mere entertainment can only reinforce what you already know because it deals in conventions and themes you are already comfortable with and know well. I suppose I am most interested in the middle area that Greenberg talked about (Stienbeck?) between high and low culture. Of course this is all before Warhol etc. made careers and set the course of art on blurring the line between avant-garde and kitsch but I feel Greenberg had some inclination that this middle area was important. After all the avant-garde is full of risks, one is that it will be misunderstood if it is too difficult and another is that it will be ignored if it is too boring. As an artist I find this especially daunting because I am constantly at odds with my dueling impulses to be avant-garde, to push myself to experiment, to be difficult and my other impulse to be more kitsch, more entertaining, to appeal to the widest audience possible. After all, to be ignored in the hyper competitive art world, where there is so much entertaining, beautiful work everywhere is a big risk.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)